Your cart is currently empty!

The Attending Theory of Motivation

Overview of the Attending Theory of Motivation

The Attending Theory of Motivation (ATM) offers a comprehensive framework for understanding goal-directed behavior in higher animals, with a particular focus on human addiction and habit dissolution. Here’s a concise summary of its key points:

Core Concept: ATM posits that all goal-directed behaviors are driven by Motive-Actualization-Cycles (MACs), which involve pursuing an “attending” (the focal experience) to fulfill underlying motives. Addiction is not distinct but a form of habitual behavior, curable through “Dishabitization”—the complete dissolution of a habit.

Addiction and Dishabitization: Unlike the traditional view of “once an addict, always an addict,” ATM suggests habits, including addictions, can be fully resolved. Absolute abstinence is not necessary; instead, controlled engagement (intermittent abstinence) via a Pruning-MAC allows for recoding of Motive-Power and Cue-Power, reducing cravings and habit strength.

Key Terminology:

- Attender: The individual or animal performing the behavior.

- Attending: The active, present-moment experience central to a habit.

- Attentive: Objects or conditions needed to actualize an attending (e.g., a cigarette for smoking).

- Motive-Actualization: Fulfilling the underlying desire (positive or negative).

- Cue-Power: The predictive strength of cues guiding behavior.

- Pruning-MAC: A conscious strategy to reduce habit strength by delaying attendings and lowering repetition rates.

Mechanism of Change:

- Habits form through repeated Attending-Actualizations, reinforced by Motive-Power (liking/disliking) and Cue-Power (predictive cues).

- A Pruning-MAC introduces a “Repetition-Ideal” (e.g., smoking three cigarettes daily) and uses Withdraw-MACs to delay attendings, creating an Outdraw-Cue (- a specific trigger for the next attending).

- This process reduces Cue-Power by decoupling habitual cues and lowers Motive-Power by aligning “wanting” with actual “liking,” akin to exposure therapy for withdrawal.

Impact:

- Cue-Power Reduction: Habitual cues lose predictive strength as conscious decision-making becomes the primary trigger.

- Motive-Power Reduction: Cravings and withdrawal diminish as the attender habituates to delayed gratification.

- Resilience and Identity Shift: The attender develops self-control, reduces habit-related self-identification (e.g., “I’m a smoker”), and fosters a growth mindset.

- Incentive Desensitization: Reverses the “wanting” dominance of addiction, synchronizing it with actual experience.

Application Example (Smoking):

Creation: Set a Repetition-Ideal (e.g., three cigarettes/day).

Maintenance: Use Withdraw-MACs to delay smoking, consciously deciding when to smoke based on the Repetition-Ideal. Exceptions are allowed but must remain rare and deliberate.

Readaptation: Gradually lower the Repetition-Ideal (e.g., three/week, then three/month) as habit strength decreases, potentially leading to abstinence or minimal, controlled use.

Human Uniqueness: Humans can consciously alter habits through cognitive control, leveraging attention-power and the desire for meaning. This distinguishes human decision-making, which blends conscious reflection with unconscious processes.

Critique and Considerations: ATM challenges conventional addiction models by emphasizing dissolution over abstinence, supported by evidence like Bruce Alexander’s Rat Park experiment, which showed environmental factors influence addiction. However, its mathematical modeling (e.g., Motive-Power equations) remains speculative without empirical validation. The theory’s complexity and novel terminology may also pose accessibility barriers.

Terminology and Phraseology: Understanding the Language of the Attending Theory of Motivation

Some terms are explained later in the text. Here is a brief introduction to a general understanding of the text.

As the existing language and terminology is often not sufficient to explain how habits, especially so-called addictions, work internally and how they can be dissolved, the development of a more detailed terminology was essential.

This terminology should make it possible to speak generically about any behavior. It can be used, for example, to make statements that refrain from using concrete, often emotionally charged or socially prejudiced terms.

Sentences such as “The smoker smokes a cigarette”, “The alcoholic is getting drunk”, “The junkie takes a shot” or – more trivially – “The person opens a door” can thus be formulated in a standardized way: “The attender actualizes an attending”.

In addition to generalization, it also serves for differentiation. The linguistic decoding of complex habitual behaviors requires a refined representation of the use of the term “goal”.

If we want to understand and describe the processes in our thinking and in our brain, we must take into account that the brain does not follow the same logic as the human being as a whole. An average person strives for happiness, while their brain strives for survival. Our brain makes us do things that it considers important. Happiness is not important for survival.

It is often counterproductive to explain our behavior using language that corresponds to the logic of our conscious thinking.

Bearing this in mind, the terminology of the ATM is intended as a basis for speaking in the language of the brain itself.

The prime example of this may be the avoidance of the term ‘reward center’. The concept of a reward circuit can be misleading. Humans may strive for rewards, but our brains do not. Brains, in contrast, seek the repetition of the events that once led to the reward not the reward itself.

What is the reward for the guinea pig if given a piece of sugar for completing a task? From the point of view of an observer, it would be the sugar, from the point of view of the guinea pig, it would be the receiving of the sugar, but from the point of view of the guinea pig’s brain, it would be the eating of the sugar. However, the enjoying of the sugar would not be an effect in form of a reward but a cause for futural reward-seeking.

According to Attending Theory of Motivation, “reward” is not the key element of reinforcement learning. Rather, it is “meaning” or “importance” in the sense of subjectively assessed significance. Assessed by conscious and unconscious thinking, manifesting itself in Motive-Power.

Furthermore, the term “reward center” suggests that all behavior is mainly positively motivated. This suggests that fears shape our motivations less strongly if at all, which is obviously not the case.

In the context of the ATM, with the term “reward”, we would be also referring to the Motive-Actualization of negative motives. The reward here would be the avoidance of negative experiences.

Dishabitization:

“Dishabitization” means the actual dissolution of a habit or also the healing of an addiction. Not to be confused with dishabituation or dehabitization.

Attender:

The attender refers to the person or animal who engages in or performs a specific behavior. In various contexts, the attender can be identified as the subject, consumer, user, smoker, addict, agent, or simply the individual undertaking the action.

Attending:

This moment of the attending is not merely a passive observation but an active interaction with the immediate environment, shaped by the individual’s underlying motives, desires, and situational context.

In the framework of habits, the attending is the core event that the attender (the individual experiencing it) anticipates, desires, and strives to achieve. It is through the attending that the Motive-Actualization process unfolds, as habits are reinforced by fulfilling the underlying motives—whether they involve seeking rewards or avoiding discomfort.

The concept of attending highlights the dynamic relationship between perception, motivation, and behavior, emphasizing its pivotal role in the continuation or dissolution of habits and addictions.

Attentive:

An “attentive” is, in most cases, the physical object of desire needed to actualize an attending. Just as ingredients must be added in the right way, at the right temperature and at the right time when cooking, so too must the attentives be selected and be actualized in the right way to actualize an attending.

Sometimes attentives are not physical, such as knowing a foreign language when the attending would be “having a conversation with a native speaker”.

Dissolvement of a habit: With this the ATM claims to offer a way to reset an attender. Even a smoker for example can dissolve their addiction and will not experience cue-reactivity and relapse if he wishes to smoke a single cigarette once in a while.

Normally, one talks about getting rid of a habit or learning to deal with it. However, in this text, the term “dissolution” is consciously used instead. This is intended to linguistically acknowledge that dishabitization is not about learning to live with a habit or addiction, but rather about completely breaking it down. Just as a substance can be completely dissolved through chemical processes.

Goals:

According to the American Psychological Association, the goal is the “end state” of a goal-directed behavior.

The ATM often uses the term “chain of cues and goals”. In addition to many subgoals, the ATM distinguishes between three main goals that mark the end of each phase of a Motive-Actualization-Cycle.

Particular emphasis is placed on the distinction between two different end goals. One is the goal of the process, the “Attending-Actualization” and the other is the goal of outcome, the “Motive-Actualization.”

Power:

This text strives for linguistic standardization of all factors influencing behavior. It attempts to define all motivational forces as far as possible as “power” and Power-Modulators.

For example, the terms “drive” or “wanting” are primarily expressed by “Attending-Actualization-power”.

Cue-Power:

The ATM defines Cue-Power exclusively via predictivity.

Feeling vs Emotion:

In everyday language, these terms are often used interchangeably. In this text, however, they are defined as follows: Feelings are the perception of bodily sensations, while emotions are the perception of sensations resulting from social bonding and interactions with other individuals or groups.

Goal-Directed-Behavior:

The ATM considers all behavior (apart from phenomena such as reflexes or tics, etc.) as “goal-directed behavior”. Every contraction of a muscle, every thought that is actively thought, pursues a certain goal-actualization. This of course applies to the conscious achievement of goals, but also to automatic and unconscious behavior.

Habitual Behavior:

A habitual behavior, a habit, is sometimes referred to as “double-processed behavior” because it involves both conscious and unconscious processes. (Caporale & Dan, 2008)

In contrast to automatism, habits are usually associated with complex chains of cues and goals. Similar to automatisms, they are a form of skill stored in procedural memory, from where they can be retrieved at will or be triggered automatically.

Most human behaviors are habitual and are presented in this text as Motive-Actualization-Cycles.

Direction-Finding-Process:

The concept of the Direction-Finding-Process is very similar to what is referred to in the context of goal-directed behavior as planning, problem solving or means-end analysis.

These concepts suggest a conscious-analytical approach, while the concept of the Direction-Finding-Process also includes unconscious factors (powers coming from feelings and emotions).

In this way, the Direction-Finding-Process can lead the individual in a different direction than would correspond to their cognitive planning or problem solving. In this case, you may be acting against your own mind.

The concept of the Direction-Finding-Process emphasizes that certain directions are not taken from a standstill. Rather, the attender is in motion at all times and merely changes direction. In contrast to active planning, the Direction-Finding-Process is therefore more of a passive process.

Motive-Actualization-Cycle:

This conceptualization is intended to serve the internal coherence of the ATM as well as the linguistically logical structure of understanding behavior.

Similar but different concepts are already in use, such as the “habit loop” and the “behavior cycle”. The habit loops described by Charles Duhigg focus on the specific components of a habit, namely cue, routine and reward. Behavioral cycles, as discussed by Howard Rachlin and other behavioral scientists, tend to emphasize the broader patterns of behavior and the interaction between short-term desires and long-term goals. (Rachlin, 2004) (Charles Duhigg, 2012)

The term “Motive-Actualization-Cycle” was created for being able to comprehensively analyze and describing what a habit constitutes of.

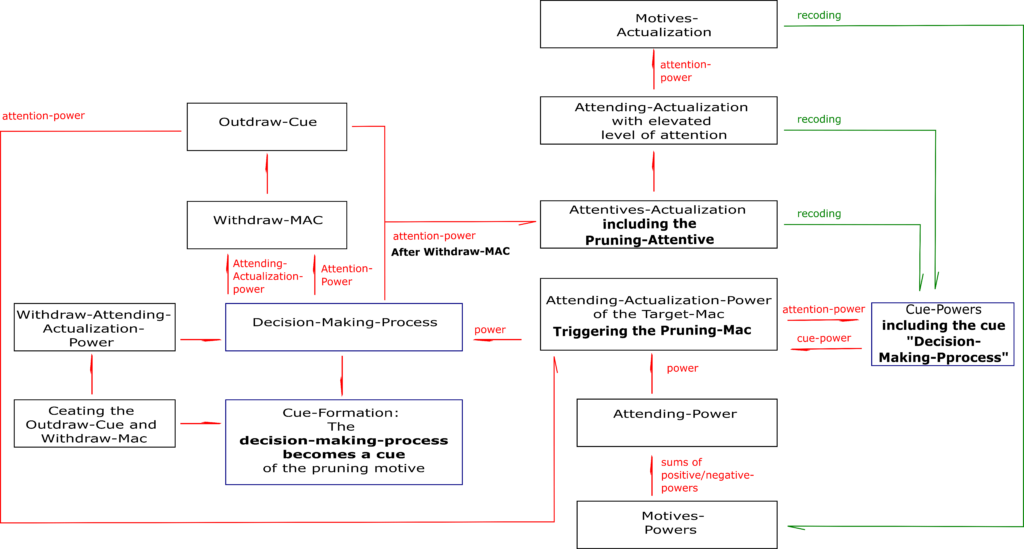

Pruning-MAC:

The ATM uses this term to allude to “synaptic pruning”. Pruning takes place when the brain continues to develop and absorb new information.

Initially, the brain forms many connections between neurons, but over time the weaker or less frequently used connections are selectively eliminated, a process known as “synaptic pruning”, which is a subset of the better known “neuroplasticity”.(Hebb, 1949)

In this way, the brain can strengthen and refine the remaining connections so that they are more efficient and effective for the transmission of information.(Peter R. Huttenlocher, 1997)

In the case of the Pruning-MAC here, however, it is the attender itself that directs the pruning specifically with its will.

In addition, it can be said that habits are being pruned by a Pruning-MAC.

Withdraw-MAC and Outdraw-Cue:

“With” comes from Middle English; “wiþ” means “against” and “draw” comes from “dragan” and means “to pull” or “to move”.

Similarly, the term “Outdraw-Cue” should mean the end of the intermittent withdrawal. To pull (draw) the Attender out of the withdrawal phase.

“The Wanting” and “the Liking”:

In the ATM, “the wanting” and “the liking” refer analogously to their use in the “Incentive Sensitization Theory” proposed by Kent Berridge and Terry Robinson in 1993. (Robinson & Berridge, 1993)

With the Incentive Sensitization Theory, the two scientists describe “liking” and “wanting” as two separate but interconnected processes that play a role in the development of habitual and addictive behavior.

In this text, “Motive-Power” comes close to “the liking” or “the disliking”, while “Attending-Actualization-power” corresponds to “the wanting”.

Brain-Time:

The brain knows no past. In everyday life, people distinguish between the past, the present and the future. For the brain, however, there are not three, but only two different states of time. The first is the “here and now” and the second is the future.

Everything is a potential future, which it constantly tries to predict. A new experience becomes a mental representation, which is a memory for the person, whose logic assigns it to the category of the past. For the brain, however, this mental representation is a potential future.

Memories are merely information that, together with imagination and creativity, are building blocks for possible futures. They are not needed by the brain as an accurate representation of what has happened – they are meant to be a representation of what is likely to happen in the future in the appropriate contexts.

Even the reality of the present moment is a potentially recurring future. Thus, every new experience is treated as cyclical. As it is made and afterwards, its value is encoded according to its importance.(Schacter et al., 2017)

In the process of MAC formation, valence coding begins at the moment the experience is made and continues afterwards, both consciously and unconsciously. Relevant events that preceded the experience are recalled from memory. Their mental representations become cues by being encoded with valence.

After the moment of experiencing the experience, from the brain’s point of view, the experience lies in the relatively distant future. Relatively distant future here means the duration of one of the MACs associated with it. Since it has just been made, the MAC, which has now entered its passive phase, must first be passed through again.

Before the experience is repeated, the entire cycle is normally run through. For example, after eating, the experience of “tasting good” becomes the distant future for the brain instead of the near past.

In contrast, when the Motive-Actualization-Cycle comes to the end of its passive phase, the experience becomes the near future. In the example above, the cycle closes with the next meal of the food that caused the “taste”. So, before the meal begins, what we would call the “past” or “memory” is the near potential future for our brain. After the meal, the cycle repeats itself, the “taste” is now again a relatively distant potential future.

The brain knows no time. When we use watches, we utilize a conceptualization of the idea that time is measurable. With Einstein we started to wrap our heads around the fact that time is relative to the individual and space. How would the brain know of such things? Brain-Time is measured in the occurrence of attendings. As the occurrence of many attendings follow certain rhythms like the circadian or the repetitive appearance of the days of the week, attendings are often liked to our concept of time.

Examples of the Use of some of the Key Terms

Simplified, the following sentence could abstract various facts and thus discuss them generically: “The attender strives for Attending-Actualization in order to actualize the motive.” Here are three possible contexts:

1) The rat (attender) presses the lever to get the sugar, consume it (Attending-Actualization) and enjoy it (Motive-Actualization).

2) The artist is painting a picture to sell to an important Art gallery to feel good about being famous.

3) The user injects heroin to get high to relieve the inner pain.

The general ATM

The general Attending Theory of Motivation is a model of how behavior of higher animals is motivated and performed.

According to the “general ATM”, behavior always has the goal of at least one Attending-Actualization, the power of which has its origin in at least one motive.

All goal-directed behavior is thus part of at least one Motive-Actualization-Cycle (MAC).

The Decision-Making-Process

Since the focus of the Attending Theory of Motivation (ATM) is on human behavior, the decision-making processes of other animals will not be explored in detail here. However, the general ATM assumes that decision-making, across species, operates on similar principles, where choices are influenced by the relative strength of various Attending-Actualization-powers.

In this framework, the body-mind complex consistently prioritizes the attending with the greatest Attending-Actualization-power at any given moment. This suggests that behavior is not random but directed toward the path that holds the strongest motivational pull, whether conscious or unconscious.

(Please see: Attending-Actualization-Power and The Special Decision-Making Process)

The Direction-Finding-Process

After the “decision” for an attending or its actualization has been made, the Direction-Finding-Process begins with the assigning of the corresponding cues and goals.

The interplay between the decision-making-process and the direction-finding-process determines which goals are to be actualized.

In contrast to the decision-making process, in which the rational mind only plays a certain part in decision-making, as do emotions and feelings, it is often dominant in the direction-making-process.

Together, conscious and unconscious thought determine this chain of cues and goals for the attender to follow. Predictive cues that occur are not only followed, but actively sought by the attender in order to succeed in the goal-directed behavior, just as a driver looks for road signs to reach their destination.

The direction along the chains of cues and goals is maintained until the goal of Attending-Actualization is reached. Exceptions to maintaining the direction can be the occurrence of unexpected obstacles or a cognitive veto.

In general, there are only two possible directions: Towards to and away from. Towards to potentially positive and away from potentially negative experiences are the two directions encoded in each motive.

All behavior is geared towards either making, repeating or avoiding experiences.

Basically, humans function no differently than a blind worm at the bottom of the sea: Good taste: Swallow down! Bad taste: Spit out! Good smell: Open mouth! Bad smell: Close mouth! Looks good: Turn towards! Looks bad: Turn away! Feels good: Move towards! Feels bad: Move away from!

The attender is driven by Attending-Actualization-Powers which are basically the sum of positive Motive-Powers minus negative-Motive-Powers. In addition, various power-modulators are influencing the result.

Normally various active MACs are influencing the direction of the attender at any given moment. (see figure 3)

There is no standstill. Even if our bodies are not moving by themselves, we are moved by the rotational force of the earth, the solar system, etc. Everything in the universe moves relative to everything else.

The same applies to present and future attending. Even when we are asleep, the Attender that we are moves in the direction of the Attending “getting up”. One of the next possible attendings in this direction would be “eating breakfast”. Perhaps “making a phone call” is another attending that we move towards overnight.

The direction-making-process navigates the attender by following the cues towards the goal of the Attending-Actualization-cycles. It is also constantly on the lookout for other cues with high predictive power to integrate into this process. The brain does not distinguish whether the attender is moving towards an attending or whether an attending is moving towards the attender.

Figuratively, you could imagine that the attender is a spaceship and the attendings are gas planets. Both would either attract or repel each other like two-pole magnets. The spaceship follows the positive attractive forces of the planets with its negative polarity in its movement.

These gas planets that could be traversed, which the spaceship would do with an attending. This would be Attending-Actualization while Motive-Actualization would be the actual influence the gas has onto the spaceship, the experience the attender has with this attending.

The gas mixture of these planets would each consist of a positive and a negative component. If the positive component is predominant, it attracts the spaceship; conversely, it exerts repulsive forces on it if its negative components predominate.

The strength of the motives would make up for the size of the planet and thus for its gravitational pull or repulsion.

The spaceship moves as if it were being controlled by two vectors: On the one hand, the vector that points in the direction that results from the sum of the attractive forces. On the other hand, the second vector is directed towards the spaceship in the direction that would result from the sum of all repulsive forces.

The Motive-Actualization-Cycle (MAC)

Every experience that the attender has experienced for the first time, sought or accidentally made, is stored in memory in order to either repeat or avoid a similar experience in the future. In generalizing terms, if the experience was pleasant, a positive motive is formed; if the experience was unpleasant, a negative motive is formed.

However, on closer inspection, one positive and one negative motive are created for each individual experience.

Since every memory is a potential future attending, the brain expects the occurrence of an attending to be cyclical, in the form of an “experience cycle”, so to speak. As each experience generates two motives, one positive and one negative (see also: The Twin-Motive) and each motive in turn generates a MAC, there are two MACs emerging from each single experience. This is why the ATM does not speak of an experience cycle but of the “Motive-Actualization-Cycle (MAC)”.

Active and passive MACs

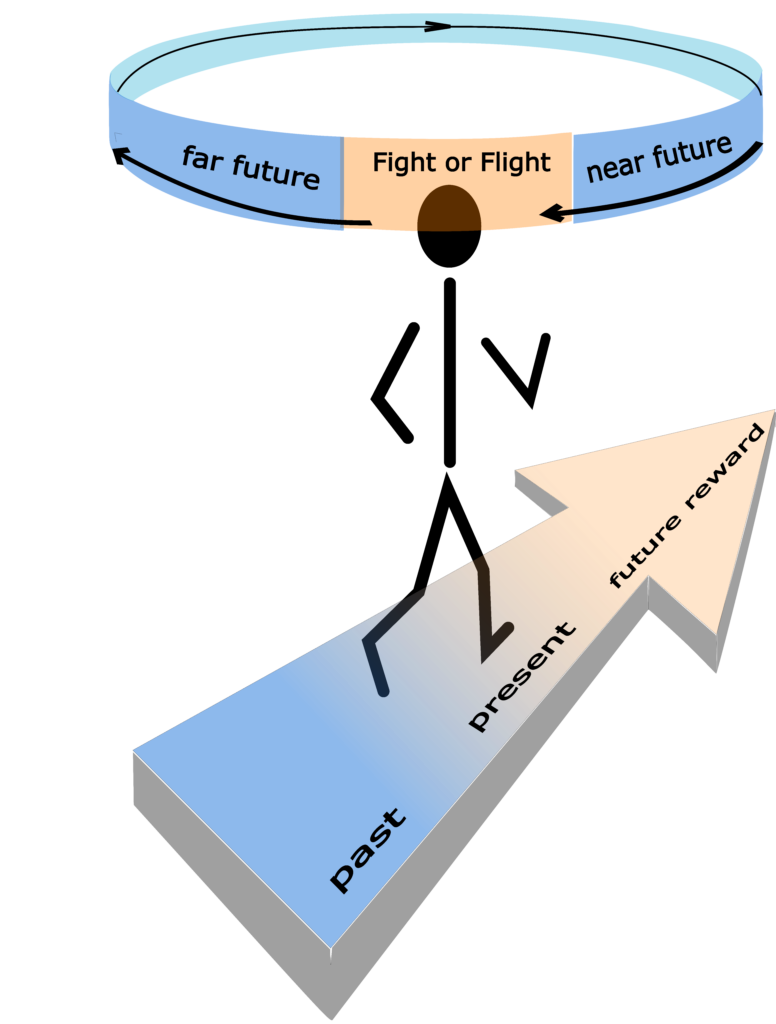

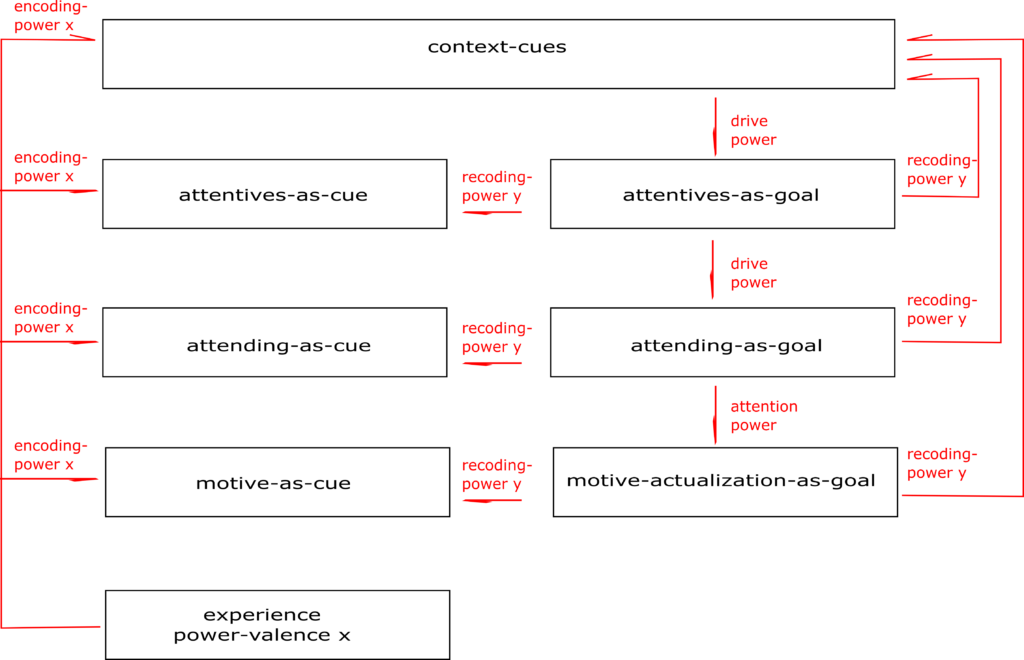

Figure 1 illustrates a Motive-Actualization-Cycle and its relationship to the attender. It aims to depict the cyclical nature of mental representations of experiences based on the brain’s logic, which often contrasts with the person’s conscious logic. While the individual’s logic perceives life as a linear progression, moving from past experiences, striving in the present, and seeking rewards in the future—the brain operates in cycles, continuously actualizing attendings in the present moment.

A black figure represents the attender. Their unconscious mind is absorbed with future attendings, only – represented by a Motive-Actualization-Cycle. Their feet are on the ground of the conscious thinking coming from the past heading towards futural rewards.

Elements of a MAC

The motive and the attending are like the head and the heart of a MAC. While the attending is what you want or don’t want, the motive is what you like or dislike. These two are the cornerstones of motivation. The other elements of a MAC serve to actualize them.

Motives

A motive is basically the imagination of the fulfillment of a wish. There are two types of wishes: Either you want something to become reality or you want something not to become reality. In the brain, a motive is a mental representation of either having a certain positive experience or avoiding having a certain negative experience.

The attender wants to repeat what it likes (positive reinforcement learning) or avoid what it dislikes (negative reinforcement learning).

Mental representations of possible future experiences are created through memory and imagination.

Each motive has a valence of importance encoded with it: the Motive-Power.

The Twin Motive

For every experience, there are not just one but two motives: a positive motive, arising from the rewarding aspects of the experience, and its negative counterpart, stemming from the adverse aspects of the same experience. These two motives can differ in strength or balance each other out, depending on their relative power.

What benefits one part of the body-mind complex may simultaneously harm another. Every actualization of a goal comes at a cost. The brain “understands” this trade-off and represents it as two conflicting motives tied to the same experience: one driving repetition and the other driving avoidance of that experience.

As a result, two Motive-Actualization-Cycles (MACs) are formed—one associated with the positive motive and the other with the negative. People are often unaware of this duality because the stronger motive usually dominates perception. Particularly because the difference in their strength normally is big. Thus, our conscience labels experiences according to the stronger motive.

The Attending

The “attending” is the main node in the network of all elements of human motivation and behavior. Linguistically, this takes into account the fact that a single goal-directed behavior pursues not just one, but several goals.

An attending can be “reading a text”, “smoking a cigarette”, “driving a car”, “eating in a restaurant” or “attending a play”. Basically, every experience, every deed and every thought are an attending.

Multiple Attendings and dual Functions

Typically, a person is involved in multiple “attendings” at any given moment. I’m riding the train holding my child and reading a cookbook and practicing my French because the book is written in French. Or I’m driving in my car thinking about you and drinking a coffee.

Exceptions to this are individual attending moments in which you are completely absorbed in the moment, in which time and self-perception seem to disappear. It is what is called “being in the zone” in sport, for example, or the gamma wave state of the human brain in meditative states. This “flow state” is characterized by a heightened sense of concentration, clarity and immersion in the task at hand.

An attending of one MAC can also be the attentive of another MAC. If eating a meal is the attending of a first MAC with the motive “satisfying hunger”, a second MAC with the motive “spending time with the family” could have the attending of the first MAC as its motive.

As a rule, different MACs power the same attending. The attending “drinking a glass of juice” can be a joint attending of MACs with the different motives “quench thirst”, “take vitamins”, “take glucose” and “enjoy something tasty”.

Attentives

An “attentive” is a means of actualization an attending. It is usually the object of desire, as it is required to initiate the Attending-Actualization.

One could speak of a kind of main attentive for a particular motive. In the case of the addiction of cigarette smoking with the “attending” of smoking, the main attentive would be the cigarette. It is what the attender subjectively identifies as the essential or necessary to satisfy their need.

Apart from that, and especially for the subconscious, there are typically a number of different attentives. All of these elements need to come together for attending to take place. In the case of smoking, in addition to a cigarette and a lighter, there would also be “a place where smoking is not considered inappropriate behavior”. There are also less obvious attentives that one would not think of unless they are not present at the time and place where attending is to be actualized. Smoking, for example, requires air, as smoking underwater is not possible. If a diver wants to smoke a cigarette, he must surface to actualize the attentive “air”.

In the case of negative motives, the object is chosen to prevent the undesirable from prevailing. An attentive could be “a weapon of defense” in case of imminent danger. It could be “a good excuse” if you don’t want to go to a birthday party to which you have been invited.

An attentive can basically be considered an ingredient in cooking, and like an ingredient, it can be used not just for one recipe, but for different recipes.

The Repetition-Rate

The Repetition-Rate represents the frequency with which a habitual attending is actualized, serving as a measurable indicator of how often a specific behavior or activity is performed. For example, working out might have a Repetition-Rate of once per day, while smoking cigarettes could occur 15 times daily. Similarly, meeting a certain friend may happen around 10 times per month, while attending the opera might be as infrequent as 3 times per year.

Cues

In psychological literature, a distinction is made between various types of cues. They are divided into intrinsic and extrinsic cues, contextual, triggering and predictive cues. The exact definition often depends on which behavior or reaction is considered and in which context it occurs.

Each cue has an encoded predictive power, a “predictiveness”, the degree of reliability to which it correctly points to a goal. This predictive power is the main factor in the likelihood of a goal being actualized if the cue is followed.

According to the ATM, the main function of cues is not to trigger the attender’s goal-directed behavior. They draw attention to a motive and trigger the decision-making process, whereby a decision can be made to follow a cue.

For the description of the MAC, a categorization into predictive and non-predictive cues is sufficient. The focus here is on predictive cues, as the reduction of their power contributes to the dissolution of habitual behavior.

Each cue is encoded with an individual predictivity. This relevance refers to a certain goal like an attending or a motive and acts as a Power-Modulator on the Attending-Actualization-Power.

Predictive cues can not only trigger the decision-making-process when they appear unexpectedly. They are also actively sought to provide clues about the direction and distance to a destination. For example, when we are hungry and don’t know where to find a restaurant in an unfamiliar city, we look for cues such as signs or walk down streets that resemble a street with restaurants in a city we know.

Like road signs that give a driver information about the direction and distance to a particular destination, cues do the same for behavioral goals. The more carefully you follow them, the more likely you are to reach your destination. And if you get lost, you actively look for them to find your way back.

A predictive cue can be linked to several goals. In the case of Motive-Actualization, these can be contradictory. For example, a picture of a candy can be a cue that not only draws attention to the positive motive of “good taste”, but also to the contradictory, negative motive of “weight gain” at the same time.

Predictive extrinsic context cues are the most obvious cues to recognize. But intrinsic cues can also be predictive cues as mental representations of context cues; they are projections from memory and fantasy onto a possible future.

They point in the direction of different destinations. If you are hungry, you might follow the intrinsic cue to a specific dish, e.g. a Chinese one. Then look for intrinsic and extrinsic cues that point to Chinese restaurants.

To achieve Attending-Actualization, the attender follows predictive cues.

Goals

The ATM speaks of a chain of goals or a chain of cues and goals when it comes to goal-directed behavior. In addition to countless intermediate steps, three main goals are distinguished:

- Attending-Actualization: The attender’s behavior is aimed at preparing and producing all things and situations that appear necessary for Attending-Actualization.

- Attending-Actualization: The attender initiates or attempts to initiate and act out the attending when all attentives are actualized.

- Motive-Actualization: While Attending-Actualization takes place, the degree of Motive-Actualization can vary greatly. It can be between zero and one hundred percent. If it is below one hundred percent, the attender endeavors to raise it to the maximum.

Each of these goals marks the end of one of the three active phases of a MAC. (see also: The Active Phase of a MAC)

Attending-Actualization is the goal of the process to get what we want, while Motive-Actualization is the goal of the outcome to like what we get.

Instead of saying, “The banana is the reward for the monkey and the goal of their behavior is to get the banana,” the ATM would rather say, “Getting the banana is the Attentive-actualization, eating the banana is the Attending-Actualization and enjoying the banana is the Motive-Actualization.”

This distinction is of the utmost importance because it is one of the keys to reversing incentive sensitization. What we think makes us happy and what really makes us happy are often two different things.

The actualization of the motive aims to repeat the good feeling that the initial experience, the first attending produced.

Attending-Actualization, on the other hand, aims to repeat the process that once produced this good feeling. Once the goal of Attending-Actualization has been achieved, this is usually enough to stop the goal-directed behavior – with or without Motive-Actualization occurring.

Processes of the MACs

Abraham Maslow introduced the concept of “prepotency of a need”, meaning that higher needs must be actualized before lower needs become important enough to seek their actualization. Maslow believed that once a need is fulfilled, it becomes less important and the next in the hierarchy of needs becomes prepotent.

There is no direct equivalent of Maslow’s “need-actualization” in the ATM, but the concept of the active and passive phases of the Motive-Actualization-Cycle comes very close to it. Here, needs are differentiated into motives, attendings and attentives according to their composition. On the one hand, a need is a motive, as motives are the mental representations of desires. On the other hand, it is an attending, as the attending represents what the attender believes will fulfill their need. An actualization of an attending can lead to the fulfillment of the need, but it does not have to.

The attendings of active MACs could even be described as prepotent attendings.

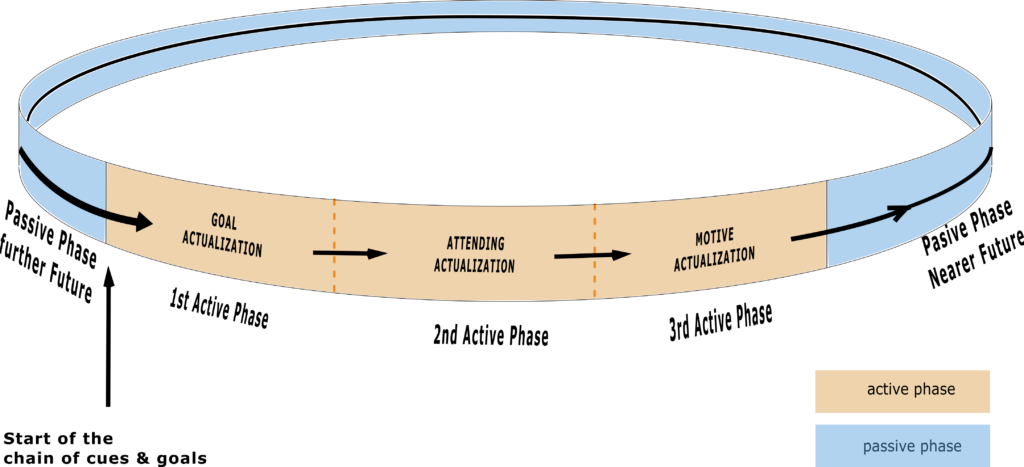

Figure 2

The passive Phase, pre-active

In the passive phase of a MAC, the attender is not pursuing goal-actualizations. In the pre-active passive phase, the MAC is maintained and kept ready, like an airplane in the hangar, to come out onto the runway when it is time to take off and enter the active phase.

Cognitive Veto

Not only can people stop themselves from initiating goal-directed behaviors, but they also have the ability to willfully stop and “ban” goal-directed behaviors that have already begun. Becoming aware of potentially negative consequences can lead to a cognitive veto. A cognitive veto can also be generated at will when the attender focuses on the potentially negative consequences of Attending-Actualization. Of course, this also often happens in an unconscious manner.

A cognitive veto is better understood as a process of strengthening the negative motives of an attending through attention-power, rather than as a specific decision being made.

It serves to prevent Attending-Actualization by focusing attention-power on the negative motives that the attending in question is also connected to. To strengthen the veto, the attender can focus their awareness on the negative consequences of the current Attending-Actualization for one thing or the positive consequences of an alternative Attending-Actualization for the other.

In order to evoke a successful veto, the attendee contemplates the various positive and negative motives for influencing the Decision-Making-Process until the direction-making process makes them take a different direction.

Due to a lack of Attending-Actualization-power after a successful veto, the “forbidden” MACs attendings disappears from consciousness, falling into its passive phase.

After the alternative Attending-Actualization is “decided” for, the brain searches for cues that are predictive for the remaining active Attending-Actualizations.

The active Phase of a MAC

After the decision-making-process has decided for an attending, allMACs associated with this attending are activated.

The active phase of a MAC has three sub-phases, each of which has its own goal. The first phase aims for Attending-Actualization, the second for Attending-Actualization and the third for Motive-Actualization.

Attentives-Actualization

In the 1st part of the active phase of a MAC, the goal is attentives-actualization.

For an Attending-Actualization “skydiving”, for example, the attender would strive to actualize the attentives “parachute”, “airplane”, “parachute training” and “sufficient drop height” among others.

Attending-Actualization

Part 2 of the active phase contains the goal of “Attending-Actualization”. A successful “attentives-actualization” has set the table for the “attending” to be actualized. However, whether the attending is actually actualized still depends on the context.

On the one hand, there could be a cognitive veto. On the other hand, the context can hinder the actualization of the attending.

In such a case, the attender typically strives to adapt the context or the attentives in order to actualize the attending after all.

If this is not possible or too much effort, the attender returns to the Direction-Finding-Process to find and start a new chain of goals for Attending-Actualization.

They can also choose to actualize another attending, which can serve the same Motive-Actualization.

Motive-Actualization

The 3rd active phase has the goal of Motive-Actualization. Motive-Actualization is either the repetition or avoidance of the experience that was originally for the positive as well as negative motive. As mentioned before, Motive-Actualization is the end goal of the outcome. (Whereas the end goal of the process of a goal-directed behavior is Attending-Actualization).

This goal actualization is not directly subjected to the goal-directed behavior. The motive can only be actualized indirectly via Attending-Actualization.

Its actualization is also not a question of yes or no. It is actualized to a certain degree, which can vary from zero to 100 percent.

The Motive-Actualization marks the end of the active phase of the MAC.

This may be the case for various reasons:

- A cognitive veto is successful.

- The cost proves to be too high.

- One or more of the attentives are used up.

- Enough Motive-Actualization has taken place so that the Attending-Actualization-power has diminished with the decreasing power of some power-modulators.

- The Attending-Actualization-Power has decreased for other reasons.

In this case, the cycle is complete and begins anew with the distant future of the post-active phase.

Passive phase, post-active

In the post-active passive phase, valence-coding changes the synaptic connections of the corresponding mental representations, goals and cues. The MAC just experienced is “played backwards” like a slide show by the brain searching for patterns: “What happened before the motive was actualized, what happened before that, and what happened before that?”

Relevant information collected about the connections between events is (re)encoded Motive-Power and Cue-Power.

After the moment of experiencing an experience, the brain sees it as a distant future, as the MAC has just entered its passive phase.

Multiple MACs

There are countless different MACs, practically one for every motive. As there are two motives for every experience an attender has had in their life there are a lot of MACs.

At the same time, however, only a few of them are in their active phase. The way the brain deals with MACs is comparable to the way we deal with completing various tasks. In part, it is even the same.

| Figure 3 |

As consciousness only ever stays with one object of perception at a time, it is constantly jumping around when multitasking. The more attendings are experienced simultaneously, the less attending-power flows into each individual Attending-Actualization. As a result, the degree of Motive-Actualization will not be as high for any one motive as it would be if it were actualized exclusively. For example, if you are simultaneously watching a profound movie on TV, eating ice cream, taking a foot bath, talking to your partner about your relationship, playing with your pet cat and thinking about why you sometimes have trouble falling asleep, you will certainly not understand everything that happens in the movie.

Nevertheless, several MACs can merge into individual ones. Eating ice cream and taking a foot bath while watching TV could develop into a habitual MAC for someone. In this example, the comforting feeling could be the motive of the three MACs merged into one MAC.

Figure 3 shows multiple MACs. One in its active phase, the other in its passive phase. An unlimited number of MACs can be active or passive at the same time.

Power Structure of a MAC

The power structure of a habitual MAC, the basic form of a MAC, is shown here. The power structures of other MACs are covered in later chapters.

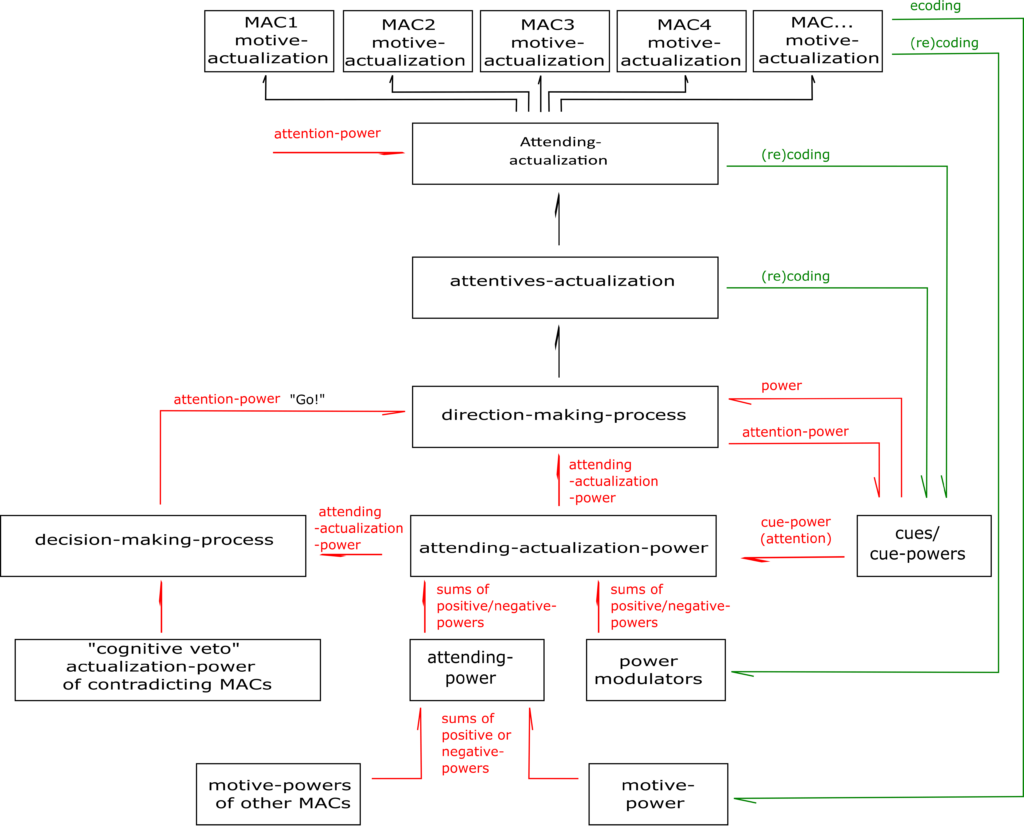

Figure 4

The Motive-Power of the MAC, together with the Motive-Powers of other MACs, contributes to the Attending-Power.

It then flows into the Attending-Actualization-Power as the main power. This can be amplified by Cue-Power and influenced by various Power-Modulators.

All MACs that share this attending enter their active phase, provided this is not prevented by a cognitive veto.

Finally, while Attending-Actualization is taking place, the power of the MAC’s motive is recoded according to the degree of its actualization.

Of course, the same applies to all active MACs that are connected to the same attending. Each motive is given an individually different degree of Motive-Actualization.

The Cue-Power of all cues for each goal in the chain of goals is recoded from the time the goals are actualized.

Motivational Powers

Motivation is commonly referred to as extrinsic (due to external factors such as rewards or social recognition) or intrinsic (due to internal factors such as personal interests or enjoyment).

The ATM does not make this distinction. According to this theory at hand, extrinsic motivational factors always relate back to the attender’s inner self.

The strength of motivation of a goal-directed behavior largely corresponds to the Attending-Actualization-power. The fundamental factor of this power is Motive-Power.

Various models, such as the Affective Tagging Model by the Dutch psychologist Nico Frijda, consider each power to be encoded with a valence of between >0 and 1.

The ATM follows their example of mathematically demonstrating the effects of motivational powers or valence coding.

Motive-Power

The origin of all motivational power of a MAC is Motive-Power. Each motive is encoded with the degree of importance of the experience that was the source of the motive. Motive-Power reflects the subjective importance of a Motive-Actualization for the attender. It is the strength of the predicted positive or negative consequence. Conscious and unconscious valences are equally the sources of this power. (see: Motive-Power-Coding).

Actual-Motive-Power

This power corresponds to the degree of actualization of the motive. It is an essential factor for recoding Motive-Power.

As Motive-Power represents the level of “liking” or “disliking” of an attending experienced in the past, Actual-Motive-Power is the degree of “liking” or “disliking” the attender experiences with Motive-Actualizations.

Attending-Power

Attending-Power is the overall importance of an attending. The strength of an Attending-Power results from the sum of the Motive-Powers associated with the attending and the strength of the connections. (see: valence-coding)

A single motive can project power onto multiple attendings, just as multiple motives can project power onto individual attendings.

Attending-Actualization-Power

The Attending-Actualization-Power is primarily fed from the Attending-Power. Terms like “drive” or “motivation” may be used in other contexts for this power. The various Power-Modulators and cues also have an influence on its strength.

The hierarchy of attendings and their pre- and post-potency results from this power.

Power-Modulators

Attending-Actualization-powers can be amplified or attenuated by a variety of Power-Modulators. This can happen indirectly through their influence on the Motive-Power as well as by affecting the Attending-Actualization-power directly.

This chapter will briefly outline some of them as there may be countless more like stress, peer influence or vulnerability to name a few.

Cue-Power as a Power-Modulator

In the Attending Theory of Motivation (ATM), Cue-Power functions as a crucial power-modulator that dynamically influences the strength and direction of an individual’s motivation toward specific behaviors. Cue-Power is defined as the predictive strength of a cue in signaling the likelihood of achieving a desired attending or goal. Acting as a power-modulator, Cue-Power adjusts the Attending-Actualization-power by either amplifying or attenuating the motivational forces that drive goal-directed behavior. For instance, a high Cue-Power associated with a particular stimulus intensifies the Attending-Actualization-power, thereby increasing the likelihood that the individual will pursue the corresponding behavior. Conversely, a low Cue-Power diminishes this motivational pull, making the behavior less likely to be actualized.

Furthermore, Cue-Power interacts synergistically with other Power-Modulators, such as identity, commitment, and rhythm-modulation, to fine-tune the individual’s behavioral responses in various contexts. Through processes of encoding and recoding, the brain continuously updates Cue-Powers based on past experiences and current environmental stimuli, ensuring that motivational forces remain aligned with the individual’s evolving goals and situational demands. This dynamic regulation allows individuals to adapt their behavior effectively, responding to both internal states and external cues with appropriate motivational intensity.

By modulating Attending-Actualization-power, Cue-Power plays an integral role in the decision-making and direction-finding processes of ATM, guiding individuals toward behaviors that maximize positive outcomes and minimize negative consequences. Consequently, understanding and manipulating Cue-Powers can be a powerful tool in strategies aimed at dissolving maladaptive habits and addictions, as it directly impacts the motivational landscape that governs habitual behaviors.

Identity

Personal identity seems to act like a gravitational force between the attender and the attending. Since the brain is an interface between the self-image and the outside world, any reference to self-related mental representations is given an extra dose of attention.

Identity and role behavior appear to be genetically inherent in species with pronounced social networks, also outside of humans. In his 1994 study ‘Investigation of Social Hierarchy in Rats Through Water Immersion Experiments,’ Didier Desor explored social hierarchies in rats under stress-inducing conditions, such as forced water immersion.” Desor placed six laboratory rats in a glass box with a tunnel staircase leading to an opening at the bottom of a tank half-filled with water. A feeder was attached to the wall of the tank, forcing the rats to swim and dive for the food. Desor observed that the rats formed a clear hierarchy in this situation:

Three “worker” rats constantly swam for the food. Two rats became “exploiters” and snatched the food from the workers instead of swimming themselves. The sixth rat became independent, diving for food alone and neither sharing nor having to share with the other rats.

In his follow-up experiments, Didier Desor investigated the adaptability of rats’ social roles when their group composition changes. When grouping rats with the same original roles (exploiters, workers or independents), Desor observed that the rats quickly adapted their behavior and reorganized their hierarchy.

When Desor placed six “exploiters” in a group, these rats were forced to adapt their behavior as they could no longer rely on the “workers” for food. Interestingly, the exploiters quickly re-established a hierarchy, with two of them becoming “workers” and swimming for food, one rat taking the “independent” role and the remaining three continuing as exploiters.

The same picture emerged when six “workers” were put together as well as with six “independent” rats. The same social structure was established again and again.

Although the original publication could not be obtained, Desor’s experiment has been cited in multiple analyses of social behavior in animals, highlighting its significance in this field.

It cannot be overlooked how strongly people’s motivated behavior is influenced by their self-perceived identity. If you look at fans who identify with a particular sports club, for example, it becomes clear what energy identity can unleash. Or somebody finding unexpectedly out about fatherhood often is a life changing factor because the man suddenly identifies as a father.

Identity is to the mind what a home is to the body. It feels safe there, is reluctant to leave it without good reason and tends to return there always and again for the rest of its life.

Smokers are a good example of this. If a smoker approaches another smoker, holds a pack of cigarettes underTheir nose and asks: “Do you smoke?”, the smoker will most certainly take one. Even if they don’t feel the need to smoke.

For the subconscious, every change in a habit is a cause for fear. Fear of losing the familiar as well as fear of getting or becoming the unknown.

Like an antagonist, the subconscious tends to underpin the attender’s decisiveness when it wants to make identity changes.

Reward Discounting

Every behavior is based on a cost-benefit equation. The closer the reward, the lower the costs. Spatial and temporal proximity reinforce the resulting “wanting”, the Attending-Actualization-Power.(Kurzban et al., 2013)

For the brain, spatial and temporal proximity are not different. The sum of the number and size of the intervening attendings is the measure of proximity.(Walsh, 2018)

Marc Lewis calls this phenomenon “now appeal” in The Biology of Desire: Why Addiction is Not a Disease. (2016, Scribe Publications)

Other sources refer to it as “resource efficiency”. In this text, the term “reward discounting” is chosen and used in the sense of George Ainslie. His theory of reward discounting differs from earlier theories in several respects.

Ainslie’s theory is known as “hyperbolic discounting theory” and is based on the idea that people discount future rewards more than traditional exponential discounting theories predict.(Ainslie, 2001)

Reward discounting is often responsible for making decisions that turn out to be bad in the long run. Favoring immediate rewards over long-term returns and discounting future benefits may sometimes seem puzzling. “Why do people smoke even though they know it will kill them?” The short answer is they don’t know. At least their subconscious doesn’t know.

Discounting rewards in daily life is often seen as a kind of weakness of the human mind. Grasping for instant gratification is a counter to delayed gratification, which is arguably one of the most important factors for success in life.

Nevertheless, the ATM considers reward discounting to be a fundamentally healthy trait. From an evolutionary perspective, various factors could have played a decisive role in the development of reward discounting as a characteristic of human personality.

The fact that the formerly reasonable characteristic of reward discounting is now considered unreasonable by modern people and has turned into something negative is primarily due to the serious change that the factor of future uncertainty has undergone.

The likelihood of dying young or unexpectedly has fallen dramatically. It may sound a little cynical, but the problem of the long-term effects of addictions, for example, is a consequence of increased life expectancy. Ten thousand years ago, people did not die of cirrhosis of the liver due to alcohol abuse. Back then, this disease could not even reach an advanced stage because life expectancy was so low that people would usually have died before then.

If you were to give a modern person aged twenty the choice of either a) having an abundance of exquisite food for three years from now, or b) a lifetime of food, but only from the age of 40, he would surely choose b). Ten thousand years ago, however,Their choice would probably have been the exact opposite.

Only our rational mind in the form of conscious thinking “knows” about the newly acquired high life expectancy. Our feelings and emotions are not yet evolutionarily adapted, so that “wrong” decisions are not a shortcoming, but something completely natural.

Attending Discounting

The more limited the availability of a resource, the more valuable it is. This applies not only to all forms of business, but also to the basic valuation by our brain. We value rare things more than what appears to be in abundance. It is not important to keep something if it is always there and available. New or rare things are interesting and at least of potential importance. Of course, the resources of necessities become especially valuable when they are limited.

This also applies to attendings. As each new experience is the only one of its kind up to this point, it has a certain significance. Attending a new MAC initially has the added value of a limited resource. The phenomenon of curiosity takes this into account.

If, over time, the attender has managed to make all attentives readily available and to have Attending-Actualization more or less at will, attending discounting sets in. The greater the abundance of resources – the easier it is to actualize an attending, the less value is assigned.

For example, in a camp near a lake in the rainforest, attending “drinking a cup of water” naturally has less Attending-Actualization-Power than hiking through the desert.

Homeostasis and Baselines

Obviously, simple bodily, emotional and rational states are waxing and waning factors of Attending-Actualization-Power.

When you’re hungry, food seems more tempting and delicious – when you’ve been around the nicest people all day, you might want to be alone for a while – when you’ve been disciplined and worked hard for 20 days in a row, you’re happy to have a day off like you might be on vacation.

Less obviously, the homeostasis of an attender’s dopamine baseline often proves to be a crucial factor in addictive behaviors.(Berridge, 2009) (Wise, 2004)

Dr. Anna Lembke is Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine. According to her, the brain’s reward system is constantly adapting to maintain homeostasis, and this adaptation can lead to changes in baseline dopamine levels. For example, repeated exposure to highly rewarding stimuli can lead to a decrease of the dopamine baseline, which in turn can contribute to the development of tolerance. She emphasizes the dynamic nature of the dopamine baseline. (Lembke, 2021)

Commitment-Modulation

Not only do we look in the direction we are going, but we also tend to go in the direction we are looking. Once we have decided to carry out a certain task, we are “determined” to continue this path.

We may have gone into the kitchen to do something – but what was it? Standing there, we seem to need to know! We want to finish this task, no matter what it was. Even though it can’t possibly be that important, we have a feeling that it must have been.

The power-modulator “commitment” refers to the motivational power that drives individuals to maintain consistency between their thoughts, beliefs, and actions. (Cialdini et al., 1995)

This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the Zeigarnik effect or cognitive dissonance. The term “cognitive dissonance” was first introduced by psychologist Leon Festinger in 1957. His groundbreaking work is based on the observation of a doomsday cult that continued to believe in its prophecies even after they had failed, which led to insights into how people deal with contradictory findings.

(Bluma Zeigarnik, 1927) (Festinger, 1957)

This innate human tendency towards commitment can strengthen an Attending-Actualization-power to such an extent that the connected MACs cannot easily switch from their active to their passive phases.

If a passive MACs Attending-Actualization-power grows to such an extent that it exceeds the strength of the currently pursued attendings, it is the commitment-power that keeps the attender on track. It prevents us from constantly changing our alignment, it prevents us from jumping back and forth between different goal-directed behaviors.

Rhythm-Modulation

The power of rhythmic repetition is obvious in nature. Almost all animals follow circadian rhythms.

Humans are rhythmic animals, probably the most rhythmic of all. The heartbeat, breathing, walking, talking, running, singing and dancing are perhaps the most obvious examples of this. Good timing provides the body-mind-complex with the optimal preparation for the routine of complex behavior or even a simple muscle contraction.

If you get up at the same time every day, you no longer need an alarm clock, and if you always eat at a certain time, you’ll get your appetite on time.

Even medicine makes use of the circadian rhythm with so-called chrono pharmacology. We organize our lives and routines in different rhythms. Daily, weekly and monthly tasks are the most common.

Moreover, attendings of all kinds seem to strive for rhythmic actualization. Anchoring them in our artificial schedules such as calendars is a question of practicality.

It is in the nature of things to facilitate reunions with friends by scheduling them for every Monday of the month, for example. Other habits can have a Repetition-Rate of three to five times a year and are not tied to specific times or dates. Their rhythm may have resulted from various homeostatic factors and necessities in the attender’s life circumstances.

Once a habit is established, its Attending-Actualization-Power is rhythmically strengthened.

Attention-Modulation and Free Will

“Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space lies the power to choose. In that choice lies your growth and freedom.” (Viktor E. Frankl, 2006)

Concentration, focus and mindfulness make up attention-power. This power is of such importance for the Attending Theory of Motivation that it could also be called the Attention Theory of Motivation.

It is no secret that focusing attention on a goal increases the likelihood of achieving that goal. Attenders can direct their attention to a specific motive or attending and thus influence the decision-making process.

According to the ATM, this is how free will flows into an attender’s decision.

As magnifying effect, the attention that the attender invests by focusing on any element of a MAC will increase its power.

Conversely, goals and cues lose power when the attention-power of the attender is taken up by other cues or attendings. This can be seen, for example, when stillness meditation leads to a reduction in symptoms of ADHD, as suggested by long-term studies.(Galante et al., 2018; Musso et al., 2016; Zylowska et al., 2008)

Valence Coding

How the brain recognizes and processes positive or negative experiences is generally referred to as valence coding. It is a value system that determines how and how strongly our body-mind-complex should react to certain things in our environment.

A MAC is a revaluation mechanism in the form of a feedback loop. The feedback of the degree of Motive-Actualization (the strength of “liking” or “disliking”) (re)evaluates the different Motive-Powers of all MACs that share the related attending. This evaluation takes place during the experience and afterwards.

During retrospective processing, the MAC is mentally repeated or even “played backwards” by the brain. Each goal-actualization causes a re-evaluation of the Motive-Power associated with it.

Two of the motivational powers are directly encoded, decoded and recoded:

1) Motive-Power: The (re-)coding of Motive-Power is caused by experiences.

2.) Predictive power: The predictive power of a cue is recoded each time it is followed.

The other motivational powers are a product of these two powers and the various Power-Modulators.

Figure 5

Since the ATM was born out of the need for an approach to scientifically explain how addictions can be dissolved, this chapter will attempt to provide a mathematical illustration of how Motive-Power and Cue-Power of strong habits can be reduced and even dissolved.

At this point, we can only speculate about the exact interplay of the various factors involved. Empirical data must be collected in order to formulate solid hypotheses about the nature of this factor.

To illustrate how decreasing of motive- and predictive-power can work, the ATM proposes the use of the weighted average, a mathematical concept in which an average value is calculated by assigning different importance or “weights” to individual data points.

The Encoding of Motive-Powers

In motive formation, Motive-Power is encoded with the subjective value of the original experience. This value has two factors, namely strength and direction.

The Motive-Power is encoded in relation to the degree of importance of the experience. This is the level of predicted liking and disliking, the degree of how strong the attender perceived the attending as physically beneficial, emotionally good and rationally as right.

Two motives are encoded for each experience with the strength of this experience-power; one of which is negative and the other positive (see also: Motives)

This gives the positive motive a valence of 0 for 0 percent importance and a valence of 1 for 100 percent importance.

Accordingly, the negative motive has a valence of 0 for 0 percent importance and a valence of -1 for 100 percent importance.

An almost life-saving experience would generate a power of approximately +1 for the positive motive. The valence of the negative motive for the same experience would depend on the strength of the negative consequences of the same experience.

Conversely, an almost life-destroying experience would generate a power of approximately -1 for the negative motive, while its positive would be characterized by the strength of the positive consequences.

Neutral experiences would not generate Motive-Power as they would not even be remembered as new experiences.

The Recoding of Motive-Power

While Motive-Power formation essentially corresponds to the liking or disliking of the original experience, the valence recoding of the Motive-Power takes place each time the motive is actualized. (see Figure 4)

The ATM proposes a mathematical approximation of how Motive-Power could be changed by Motive-Actualization. (see Motive-Power-Equation in the appendix)

Encoding and Recoding of Cue-Powers

The predictive power of cues is encoded in valence after a significant experience has been made. The brain strengthens the neuronal connections of memories that arose with the experience in a temporal or meaningful context.

All events that preceded the new experience are potentially remembered as cues. These mental representations are linked to the experience as such. The strength of this connection becomes the Cue-Power.

Every time a cue is followed by the attender for goal-actualization the Cue-Power get recoded no matter if one or more goals will be actualized. Even if no goal is actualized its predictiveness will get recoded. All it takes to recode Cue-Power is that the attender follows the predictive cue.

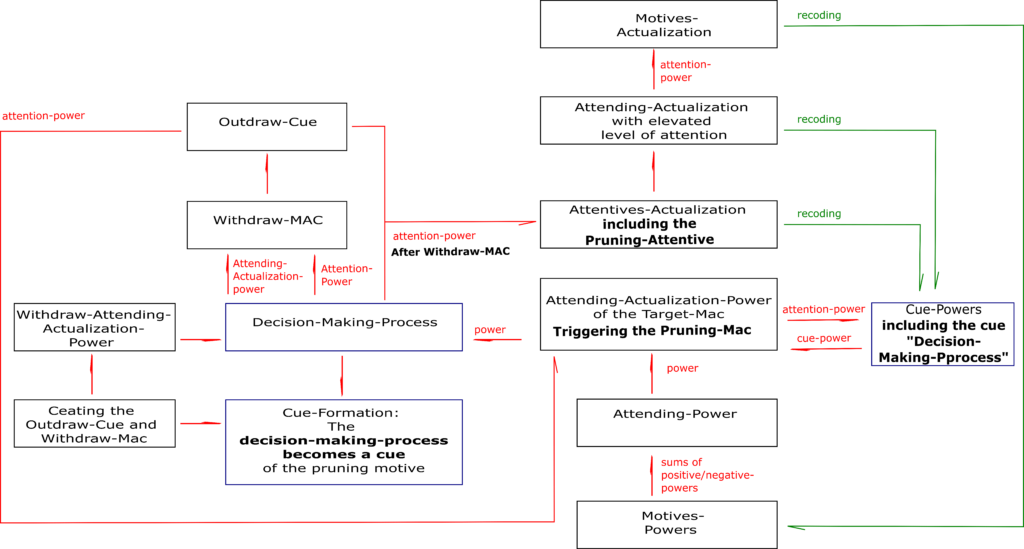

Figure 6

The special ATM

The “special ATM” builds on the “general ATM” and expands it by one level. On this level, the level of human behavior, goal-directed-behavior can have the goal of changing itself.

It is therefore about the special case in which the motivation of an individual’s behavior is to change the behavior of the individual itself in a certain direction, in accordance with their own reason. Here, the behavior becomes an object to itself – a specialty of our species.

Among other things (see also: Effects of a Pruning-MAC), the special ATM aims to provide a scientific explanation for reversing the process of incentive desensitization. It proposes a way of “incentive desensitization” to not only cope with “bad” habits and addictions through abstinence, but to actually dissolve them.

To achieve dishabitization, the attender must (re)gain conscious cognitive control over the decision-making process. The term “conscious” and not “cognitive” is the most important key to gaining control. Every attending must be preceded by a conscious decision.

A second important factor in addition to the conscious decision is the postponement of the next attending. The attender inserts at least one event between decision and attending. (See: withdraw-attending) Each time “the wanting” to perform an addictive behavior arises, the attender does not decide “yes” (uncontrolled behavior) or “no” (abstinent behavior) but creates a mental image of the transition from withdraw attending to the next attending. This “Outdraw-Cue” can be a specific point in time, an unrelated event, certain circumstances or simply the completion of a task before the next Attending. The length of the deferral can be anything and be from moments, minutes or hours to days, months or even years.

This approach can be seen as a form of systematically delayed gratification. The attender usually starts by delaying an attending just a little. Over time, it can increase the delay time and thus reduce the Repetition-Rate of its habitual behavior.

This process replaces automatisms and habitual reactions with conscious decisions. The more consistently this approach is pursued, the more reliably the Cue-Power decreases. In addition, the Motive-Power for habitual behavior decreases, as “wanting” and “liking” (re) synchronize a little further with each Motive-Actualization.

This approach differs from abstinence approaches primarily in that it considers occasional Attending-Actualizations to be not only acceptable but even necessary. Only by Motive-Actualizations can cue- and Motive-Power be dissolved and thus habits and addictions be dishabitized.

Homo Sapiens, the special Animal

Various characteristics make us a special animal that is different from all others. One of the domains in which this is particularly evident is the formation and breaking of habits.

Only we can reject the status quo that constitutes our learned behavior and change it to what we ourselves consider to be better. The ability to make cognitive decisions consciously and deliberately enables people to consciously change habitual behavior.

People value meaning: subjectively perceived meaningfulness, even if it may often be irrational, is a motivational power that can override all others in certain contexts. It is rated as important not only by the conscious mind, but also by the subconscious. Meaningfulness releases dopamine and thus causes attention-power.

People strive for happiness: “If only, if only – then I would be happy”. But whenever we get what we think will make us happy, happiness doesn’t last long.

Human beings are aware of the fact that they must die one day. This awareness of mortality plays a role in the subjective definition of “good” and “bad”, “right” and “wrong”. Thinking about mortality can trigger fear or create wisdom in a person who recognizes that everything the mind can grasp is ultimately transient. Equally, the awareness of being mortal can lead to great foolishness. It can fuel the fear of insignificance which, in denial of this fact, can lead us to ridiculous actions such as achieving fame.

Other animals do not usually become addicted, as the motto of the Nobel Conference 51 on addiction expresses: “Addiction – a uniquely human condition”(Gustavus Adolphus College, n.d.)

Other examples of this uniqueness are identification with a self and with social roles, the tendency to create self-fulfilling prophecies, the fear of fear or the desire for desire.

The special ATM is an attempt to understand and describe human behavior motivated by the desire to change oneself through cognitive control.

The special Decision-Making-Process (How Humans decide)

One of the defining traits of humanity is the ability to make conscious, rational decisions. Unlike other animals, whose actions are primarily guided by instinct and learned behavior, humans have the unique capacity to reflect, analyze, and project outcomes. This enables deliberate, goal-directed choices that transcend immediate impulses.

Two Pathways to Decisions

Decisions arise through two distinct pathways:

- Conscious and Reflective Decision-Making:

This involves deliberate thought, weighing options, and considering long-term consequences. It is a hallmark of human cognition, grounded in the ability to use language, imagine possible futures, and align actions with abstract goals.

- Unconscious Evaluative Decision-Making:

These decisions stem from the body-mind complex’s automatic processes. Operating largely beneath conscious awareness, this pathway integrates instincts, emotions, and past experiences to produce rapid evaluations. It is a shared mechanism across the animal kingdom, ensuring survival through swift, often intuitive responses to the environment.

The Dual Process in Action

The Attending Theory of Motivation describes decision-making as the interplay of these two pathways, where conscious reflection and unconscious evaluations converge.

The Role of Attention-Power:

Conscious decisions rely on the ability to focus attention deliberately. This attention-power sharpens the attender’s ability to evaluate options and strengthens the commitment to act in alignment with their goals.

- Unconscious Contributions:

At the same time, unconscious processes influence the decision-making process, offering insights drawn from emotional and bodily states, habitual patterns, and prior experiences. These inputs can harmonize with or challenge conscious intentions, creating a dynamic tension that shapes the final decision.

Attending-Actualization-Power as a Synergistic Force

At the center of the Decision-Making-Process is Attending-Actualization-power—the attender’s capacity to actualize intentions into actions. This power emerges not solely from conscious focus but from the synergy of willpower and unconscious support. When attention is directed toward a goal, it creates momentum, but the actualization of that goal depends on unconscious patterns aligning with conscious intent.

It is this interplay—not conscious control alone—that drives successful decisions. While a strong focus enhances Attending-Actualization-power, the attender must also acknowledge and work with the influence of their subconscious to fully align their behavior with desired outcomes. (also see: The Triune-Control Hypothesis)

The Special Attending Theory of Motivation posits that effective decision-making involves a dynamic interplay between these two processes in human beings. Conscious and unconscious elements combine to determine actions, with each influencing the other to varying degrees depending on the context.

When the attender channels their attention onto what they deem to be the “best choice,” they reinforce the Attending-Actualization-power, increasing the likelihood of delaying the executing the unwanted behavior.

Dishabitizing a habit like smoking requires aligning conscious attention-power with a reconditioning of unconscious patterns. The stronger the focus on the Outdraw-Cue, the more Attending-Actualization-powers are influenced.

While willpower is often seen as a finite resource, the Attending Theory of Motivation reframes it as a skill—one that grows stronger with intentional practice. By repeatedly directing attention to align with desired goals, the attender builds both focus and the ability to actualize their decisions effectively.

The chapter concludes by emphasizing the empowerment that comes from understanding and mastering this process. With practice, individuals can leverage both conscious and unconscious decision-making to create meaningful changes in their lives, aligning actions with values and long-term aspirations.

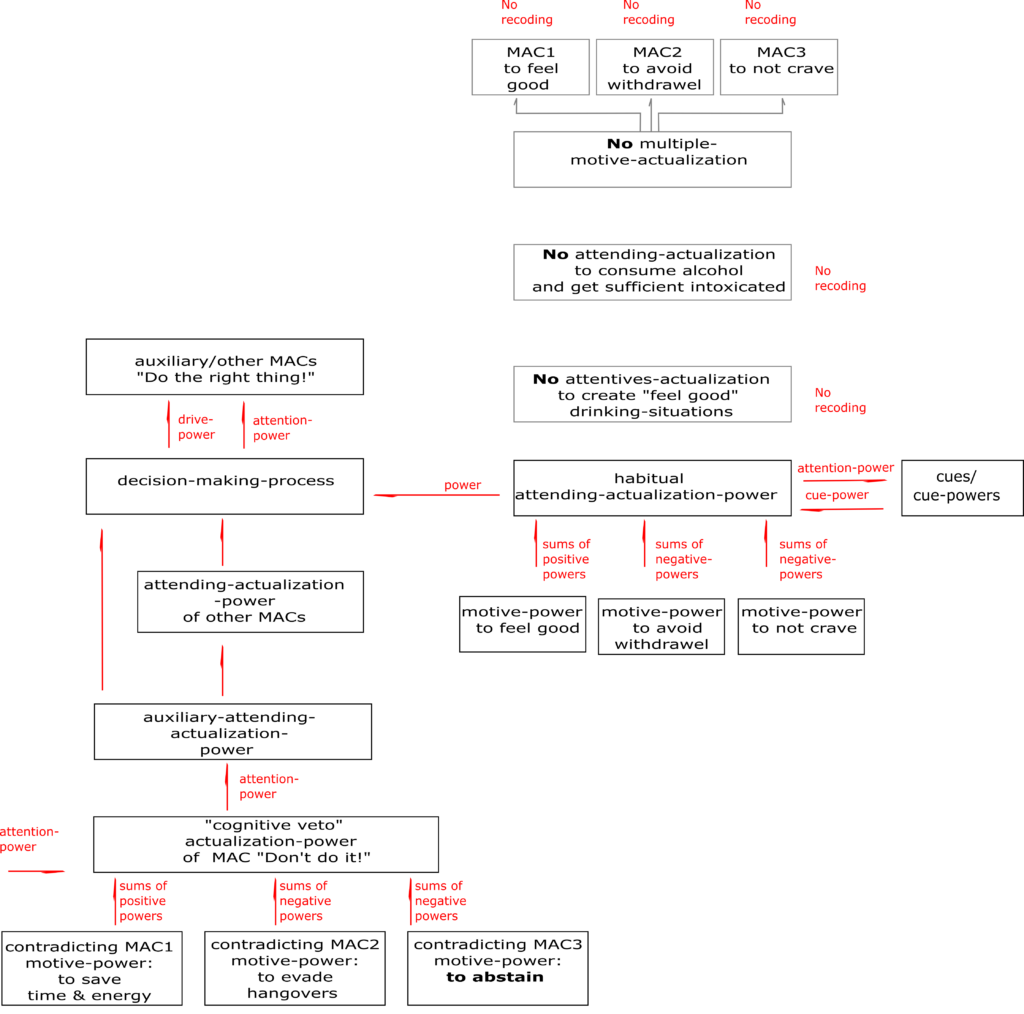

The Corrupted-Attending

The root of bad habit and addiction is typically a “Corrupted-Attending”. An attending becomes corrupted when a new motive develops from its repeated actualization.

For example, in habitual alcohol use, a new negative motive may be withdrawal, while the original motive was socialization.

Because both motives have the same attending as a cue for their actualization. Thus, these two different goal-directed behaviors are easily mistaken as one, namely “this person’s drinking behavior”.

However, these are two different MACs with two different motives. The original, positive motive is to feel good. The new, negative motive is not to feel bad.

Once the negative motive is established, it reinforces the behavior. This happens even if the original, positive motive is no longer actualized.

Experiencing withdrawal and carvings leads to new, negative motives aimed at avoiding these feelings. A new MAC is created with each new motive.

Such a MAC with a corrupted, negative motive can become more potent than the original from which it was created.

The liking of the effect decreases, while the desire to dissolve feelings of withdrawal increases.

After habituation and building up tolerance, the attender may no longer be “rewarded” with good feelings from drinking. However, the desire for these good feelings becomes stronger with each failed attempt to feel good. Along with the feelings of withdrawal, the “craving” to get intoxicated becomes stronger and stronger.

The attender gets into a vicious circle as the new motives have to be actualized by the original attending, the “drinking of alcohol”.

However, several new corrupted motives can also form. They can be both negative and positive. In the case of alcohol consumption, the original motive may have been “socialization”, which may have led to the regular Attending-Actualization “drinking”. Over time, both the negative motives “withdrawal”, “shame of being a drinker” and “loneliness” and the positive motives “forgetting everyday worries”, “feeling at home in the local pub” and “getting support from relatives” may also have developed as new motives. These new motives share the same attending, the Corrupted-Attending.

The Abstained-Attending, “Abstinence”

What is recognized as “bad”, “wrong” or “harmful” behavior is either controlled or stopped altogether. To avoid negative consequences, a MAC can be stopped by a rational veto while it is still in the passive phase of the decision-making process. Of course, this is also possible during the active phase, although this usually requires the activation of another contradictory MAC. (see also: Cognitive Veto)

Figure 7